Moldova: where energy is inseparable from geopolitics

This country landlocked between Romania and Ukraine has seen its energy supply chain turned upside down since war began on its doorstep. Could this be the time to become more energy independent?

Europe as a continent is pretty well defined to the North, West and South by its coastline (and yes, the British Isles, you’re also part of the club ;) ). To the East, the question gets tougher. Geography books in school kept mentioning the Ural and Caucasus mountain ranges in Russian territory as self-evident limits to Europe. Culturally, the answer seems anything but self-evident, at least when looking at the Eurovision, the FIFA Euro cup, and, on a much more serious note, the Russo-Ukrainian war that is currently unfolding.

A country which is inevitably affected by the latter is Moldova: landlocked between Romania and Ukraine, this country of 2.5 million people finds itself caught in the middle of the biggest geopolitical shift which Europe has experienced in decades. In fact, this isn’t the country’s first gig when it comes to dealing with its bigger neighbours. Way back in the days, Moldavia was a remote Eastern province of the Roman empire, which explains why a majority of its population still speaks a Latin language, Romanian. Along with the Principality of Wallachia and Transylvania (yes, the one from count Dracula), the Principality of Moldavia came to become one of the Romanian speaking states in medieval Europe, sealing the unique identity of the local population by blending this Latin language with the Slavic cultural sphere of its neighbours. Since then, the region was controlled by the Ottomans (Turks) and then the Russians, before really gaining back its independence only after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 (see here for more context).

Like many countries in Eastern Europe, it has since then slowly learned to stand on its own two feet, establishing a government within a parliamentary republic. The country had also in recent years tried to step away from the Russian sphere of influence by electing the pro-Western Maia Sandu in 2020 and applying for EU membership. One thorny issue however remains to this day: Moldova’s energy independence. In this post (sorry for the many sidelines until now, it’s been a long but necessary contextual introduction), we’ll be looking at Moldova’s energy supply, how it affects its relationship with its neighbours, and how the energy transition could affect these dynamics.

Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine started in February, only 20% of its energy demand was met by local production, which mainly consisted of solid biomass for residential heating, i.e. wood. While renewable, wood is not really the kind of energy used for transportation, and wood chimneys in an urban environment doesn’t sound that desirable either, without mentioning the debates around the air quality and sustainability of burning wood. Leaving wood aside, this leaves Moldova with a complete dependence on imports for its energy supply… Until before the war, nearly all gas imports came from Russia and the country also imported all of its oil.

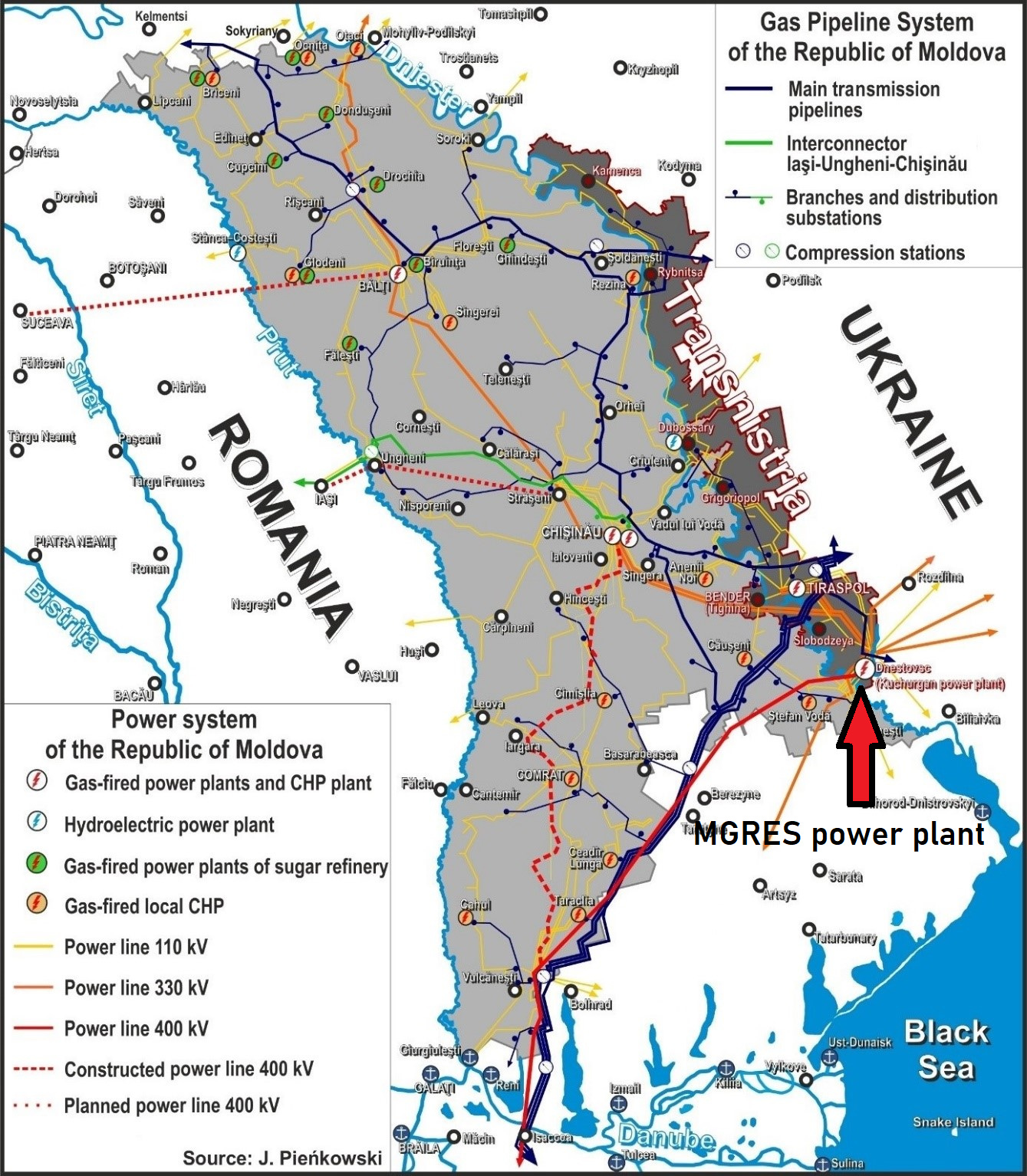

This is where it is time to bring Transnistria onto the table, just to make things a little bit more complicated. Transnistria is the region to the east of the Dniester river, bordering Ukraine, with an important Russian minority. While the rest of Moldova became independent in 1991, this region refused to let go of its ties with Russia, causing a separatist movement and an ensuing war. Since then, the question of Transnistria’s independence from the rest of Moldova has never really been resolved, but it operates de facto as an independent republic benefitting from Russian support, including military troops and … free gas. This has allowed the region to run its largest factories, amongst which a steel mill, a cement plant, and, most importantly for us, the Kuchurgan gas power plant, also known as Cuciurgani-Moldavskaya GRES (MGRES), which has a nominal capacity of 910 MW.

The importance of this power plant is critical: before the war, it generated 75% of the power consumed by Moldova (55% if excluding Transnistria). The rest of the electricity consumed in the country was largely imported from Ukraine, with only 20% generated by small Combined Heat and Power plants (running on biomass?). All in all, Moldova therefore imported 80% of its electricity either directly or indirectly from Russia or Ukraine.

Wrap-up 1: Moldova has been extremely dependent on foreign imports for its energy supply, particularly from Russia. The situation has been even more fragile due to the important role of the separatist region of Transnistria in supplying electricity to the rest of the country.

As you can imagine, many of the statistics mentioned above quickly became irrelevant as soon as the Russian invasion spread havoc to the regions’ energy supply chain. In fact, a nerdy power grid anecdote illustrates the undergone changes quite well. The European power grid is divided into different regions called synchronous areas, within which power plants and loads connected to the grid oscillate at the same frequency of 50Hz. To exchange electricity between different synchronous areas, power must first be converted from AC (alternative current) to DC (direct current) and back to AC on the other side to synchronise the power oscillations with the new area. Electricity exchanges are therefore easier within the same synchronous area. On the other hand, power plants within the same synchronous area are dependent on each other to maintain overall stability in the grid, an equilibrium game which is tough enough under normal circumstances. To put it shortly, you would rather share your synchronous area with friends than with foes. And guess who Moldova and Ukraine shared their synchronous area with before the war broke out? Correct, Russia.

In fact, plans to disconnect from the Russian grid and join the continental Europe synchronous area had been in the making for a while. On the night of the 24th of February 2024, Ukraine and Moldova were starting a 72-hour test run to operate in island mode cut off from Russia, a first necessary step before connecting to the rest of Europe. Four hours later, Russian troops started the invasion of Ukraine. What initially was meant to be a 72-hour test ended up being three weeks, after which Ukraine and Moldova connected to the continental European synchronous area following an emergency synchronisation protocol, achieving in three weeks what usually would have taken months of testing and validation.

This successful interconnection with the European grid has allowed Moldova (and Ukraine) to import electricity from its southern neighbour, Romania, and the entire southeastern European region more generally. A similar dynamic is being observed in the gas sector, where the completion of the Ungheni-Chisinau gas pipeline in 2021 between Romania and Moldova has allowed to reduce Moldova’s dependence on Russian gas imports through Ukraine. While salutary, these European imports remain much more expensive than the power historically purchased from MGRES: bilateral contracts with Romania reach €110 / MWh and additional power purchased on exchanges can reach €300 / MWh , which clearly stings a bit compared to the €63 / MWh historically paid to MGRES.

Most recently, Moldova’s vulnerability regarding its reliance on Russian gas imports has been brought to light by the ongoing Transnistrian energy crisis which started in January 2025. On the 1st of January 2025, Russian-subsidised gas stopped flowing to the Transnistrian border, as Ukraine (understandably) did not extend the permission to transit gas through its territory to Transnistria. Transnistrians were left with unheated homes for several days at a time, in the middle of winter. On the 14th of February 2025, a temporary agreement was found to import gas from a Hungarian company through the rest of Moldova, with gas payments funded by Russian loans. Since then, the Transnistrian government has called a series of states of emergency, the latest (to this day) having been called on the 11th of June 2025 for 30 days, each time scrambling for new alternative supply routes. However this crisis unfolds, I think it is safe to say the current situation is not sustainable, and alternative solutions will have to be found.

Wrap-up 2: Moldova, together with Ukraine, managed to connect itself to both the European electricity and gas network, giving it access to alternative (although more expensive) energy supply routes avoiding Russia. The separatist region of Transnistria, whose gas supplies from Russia have been cut off by Ukraine, has switched from supplying to importing energy from the rest of the country.

Speaking of sustainability, what role can renewable energies play in Moldova’s energy politics?

Moldova’s uptake of wind and solar energy has been slow so far compared to the rest of Europe, the competition of cheap electricity from Russian-subsidised gas power plants probably not helping. However, the war once again seems to have brought things into action. In 2018, the total capacity of wind installations reached 27MW, while solar power reached 4MW. To give a sense of scale, 27MW corresponds roughly to 9 wind turbines… Since then, the country has reached 580 MW of renewable capacity by December 2024, of which 395 MW of solar and 161 MW of wind.

Although this growth might seem impressive, let’s remember that it is mainly symptomatic of a nascent industry: the average solar farm project in the country being around 50 MW, completing a single project in the year would already increase the country’s capacity by 10%. However, there is no sign for this trend to reduce: the last tender run by the government in 2025 for 165 MW of allocated capacity saw 444 MW worth of bids being submitted, mainly by national actors.

But what do all these numbers mean for Moldova’s energy supply? Let’s take the total wind capacity shown in the table above (160 MW) and the total solar capacity excluding net metering (280 MW: this corresponds to the solar power injected in the grid. Self-consumed electricity remains invisible in most national statistics). Let’s multiply these values by the capacity factor of wind and solar (the average amount of their capacity actually used to generate power, due to wind and sun conditions not always being optimal): for wind, the closest I found was the average onshore capacity factor for Romania given by WindEurope, which lies at 15%; for solar, I will stick to the 20% rule of thumb. Multiplying the obtained average hourly energy production by the number of hours in a year, we obtain 212 GWh for wind and 491 GWh for solar, giving a grand total of 702 GWh of renewable production over the year. When looking up the real numbers to cross-validate my estimates, I found wind + solar production in 2024 in Moldova was 691 GWh (16.7% of national consumption excluding Transnistria). Close enough for a first approximation.

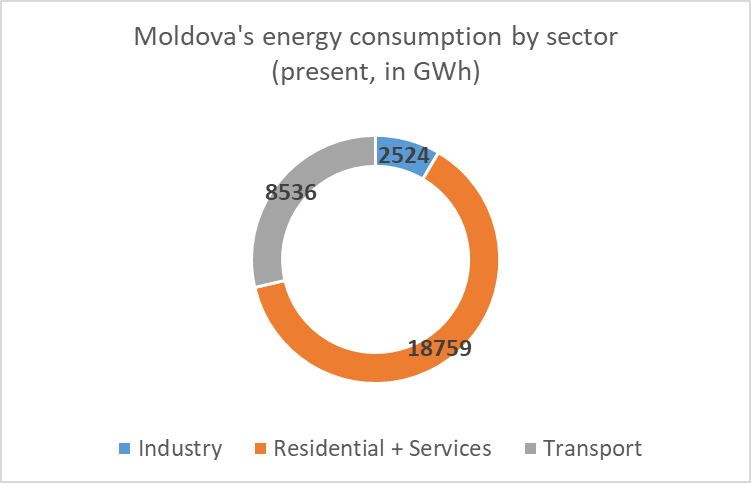

So let’s try to reuse this method in a hypothetical context where Moldova avoids any fossil fuel imports by electrifying its entire energy consumption (in residential households but also transportation, industry, and services). The current final energy consumption by sector is shown below:

This amounts to 29 800 GWh in total. After electrifying all technologies (for example using electric vehicles instead of combustion engines, heat pumps instead of wood ovens, etc.), and following the energy efficiency ratios by sector presented in this Sustainability by Numbers article, we obtain the following graph:

After electrification, the total amount of electricity consumption obviously increases, but the total final energy consumption actually falls to 14 400 GWh. To cover this entire energy demand entirely with renewable electricity, it would require the current renewable electricity production to be multiplied by 21. On top of that, Moldova’s industrial activity is still underdeveloped. If the economy were to take off, this sector could require even more energy production. As impressive as renewable’s growth is, it is hard to see how it could develop fast enough to allow Moldova to gain independence from foreign fossil fuel imports within the next few years. Neither is it necessarily desirable, as the roll-out of renewables will necessarily require interconnections with bordering countries to allow for the exchange of electricity in times of over- or underproduction. The required efforts might therefore not be as colossal as it initially seems, but even achieving a 50% energy independence in the next few years would already require a several-fold increase in capacity build out.

Wrap-up 3: Renewables have been progressing in recent years but are still at an early stage. Electrifying the country to achieve greater energy independence would require a considerable step-up in the build-out of additional renewable capacity, with corresponding interconnection to neighbouring countries.

Final remarks: Moldova is the perfect example of how energy independence or the lack of it can seal the geopolitical fate of a country. As the country is turning westwards to diversify its energy supply, it must ensure together with its neighbouring countries, and Europe more generally, that sufficient grid infrastructure is in place to appropriately be interconnected with the rest of the continent. This integration into the European energy system must of course also be done affordably. Countries like Moldova with lower GDP per capita than the European average cannot afford to be exposed to the same prices as other European countries. Tailor-made bilateral agreements should therefore be signed before throwing the country into the European internal market. In parallel, European coordination should also help the country build out its renewable energy capacity, while ensuring the local population also benefits from the renewable industry’s supply chain. All in all, as small as Moldova may be, it might be an opportunity for Europe to reaffirm the values it stands for, without sending a single military troop. If you ask me, that’s worth a shot, particularly if it doesn’t involve a gun.